Flower Lounge (9) ---- Lower Circle

- James Tam

- Aug 11, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

Along both sides of the steps linking the two Circles at Tong Fuk were similar looking bungalows housing various workshops, dining halls, sleeping quarters, a laundromat, and an infirmary. Painted white and baby blue, they looked incongruously innocent, uniformly unimaginative, suggesting a template design traced by gin-tonic drinking government architects in white linen suits from a previous age.

The last few steps of the stairway extended laterally into semi-circles, forming an amphitheatre with the bottom concourse. At the far side of the amphitheatre was a narrow footpath. Turning left on it, barely a minute’s walk away, was a hard surface football pitch visually open to the unreachable beach. To the right of the concourse was Workshop Five. Next to it was the Fan Tong Common Room. In triangulation with Workshop Five and the Common Room, about twenty phlegmatic steps away, was my dorm. Shaded by giant banyan trees, skirted by wild flowers, this secluded enclosure could have been a sub-tropical retreat if not for the omnipresent fences. Together with the football field, they formed the confines within which I ate, slept, worked, and exercised.

Workshop Five was my entrance to the Lower Circle community.

As I approached, an officer perched on a grey wooden stool laid down his newspaper. He studied me briefly, then pulled a registry from under the lectern.

‘Gong Si?’ Company?

Once again, I stalled.

My business associations were not secret. But revealing it to a stranger under the situation did not seem appropriate. Didn’t need the Guardian Angel to tell me that.

Hesitation was once again an adequate answer.

‘No?’ He entered my name in the column for inmates without Triad affiliation. The Car Thief had not taught me that one at LCK.

Gong Si means company, a commercial entity. I learnt much later on that the term originally referred to ‘Triad organisation’ in the Qing Dynasty. Triads were underground revolutionaries, not free traders, dangerous felons in the opinion of Emperor and invaders alike.

Inmates with company affiliation were grouped under three conglomerates: Number, Wo Kee, and Lo-Chiu/Sun Yee On. Not exactly fearsome brandnames for mobsters, especially Number, which sounds like a Bingo Club for hearing-aid wearing veterans.

In my secondary school days, when gangsters were ‘teddy boys’ with self-inflicted greasy hair, Number was called 14K. At some point in late 20th century, the number four suddenly and inexplicably became a taboo because it rhymed, as it had for millennia, with death. And fourteen, Sud Say, is sure death in Cantonese. Very inauspicious, especially to a gangster. Thereafter, four gradually disappeared from buildings (which were already missing the thirteenth floor due to a British aversion), seats, price tags, lockers, anything numero, to dodge death. A thirty-storey building in Hong Kong is physically only twenty-six tall after taking four, thirteen, fourteen, and twenty-four out of existence. 14K was rebranded to Number to retain the historically numeric image, but without the unlucky fourteen. A silly brandname for a gang of outlaws for sure, but silliness is preferable to sure death.

Hong Kong was a diverse community with many assemblies of underground thugs. These miscellaneous delinquent congregations were summarily lumped under only three banners in Tong Fuk to streamline identification and management. I wonder where Joe, the start-up gangster at LCK , founder of a new company, was assigned to.

The populist method used by ancient tribes to pick chieftains had been adopted by imprisoned gangsters, and worked reasonably well. Heads of the three holding companies were democratically endorsed by their respective memberships — one thug, one vote. The chosen leaders were automatically elevated to the ruling class, and became foremen and checkers at the workshops, getting paid at the top end of the scale, exempted from manual labour.

A minority of unaffiliated inmates — like myself — were the pariahs.

I, a harmless old man, new and dumb, no affiliation since retirement, walked into Workshop Five to commence my career as junior prison labourer with due meekness.

A quick glance around the room, head slightly lowered. Didn’t detect any vicious looking face.

A gang-boss greeted me: ‘Ah Cheong? Call me Ah Gou (O Dog)’

‘Gou Gor,’ Big Brother Dog looked to be in his twenties.

‘Follow me.’

At the back of the room was a matrix of cubbyholes approximately 30 by 30 by 30cm deep. A see-through plastic door, translucent from age, dangled from its last hinge. It befitted my lowly status perfectly, no complaints.

‘Thank you, Gou Gor.’

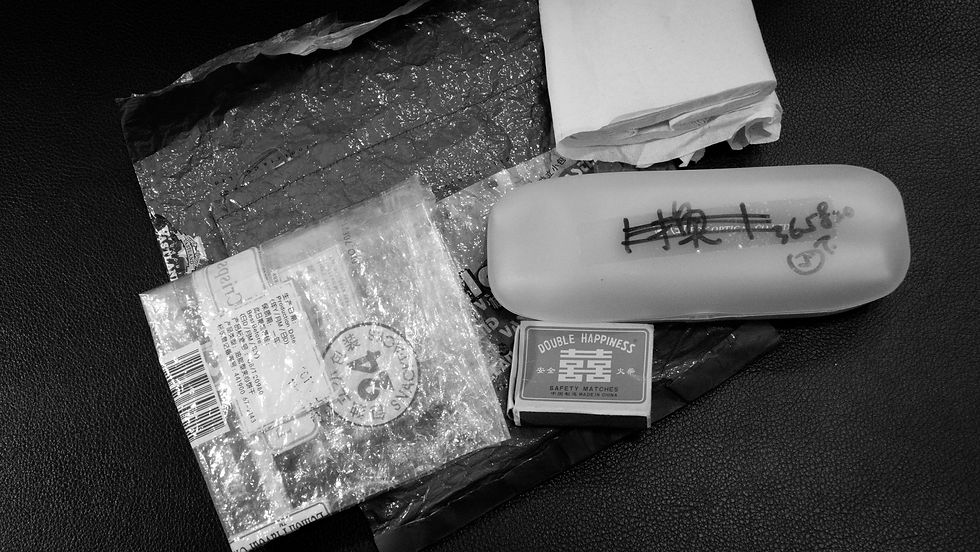

I offloaded my shampoo, liquid soap and two notebooks to the un-lockable locker. Had been hauling them around with my pens, tissues, mug, spoon, toothbrush, soap, electric razor, batteries, bug repellent. The thin plastic bag had been stretched thin at various points by the sharp corners of these objects.

A young man in front of the cubby holes noticed the pathetic state of my luggage: ‘Ah Suk — uncle — your bag’s gonna break soon.’

‘I know.’ Smiling, embarrassed by my shabby state of existence in a respectable institution.

He reached under his sewing machine and took out a conforming, B4 size translucent plastic portfolio, something which I planned to purchase with prison salary one day. But this was only my first day of work. Payday would be at least a month away.

‘Here, take this!’

‘I don’t have anything to pay you yet,’ I said, caressing the beautiful clutch bag made of cheap plastic, smelling like gum boots after a nice walk in the gutter. I didn’t have a single cigarette or biscuit, the global currency of the realm.

‘Don’t worry.’

‘You sure?’ I accepted it with eternal gratitude, pinching and twisting the Guardian Angel’s lips before it whispered anything infuriating. The snobbish ecclesiastical eunuch didn’t understand friendliness and generosity from the fringe of the human world.

‘I’m Ah Cheong. Will pay you back when I get paid.’

‘Call me Ah Kin.’

No handshake.

Just like that, I looked semi-respectable ahead of schedule, and made a new friend. I folded the old plastic bag carefully and put it in my locker.

A well-mannered young man came over and introduced himself as Xiu Long — Little Dragon — addressing me Uncle Cheong. He was one of the gang foremen. Moderate in stature, he was well-built and handsome with a hint of mixed blood. He told me to sit at a table near the entrance. I took the opportunity to enquire about the toilet paper situation. He said one roll per person was rationed every three weeks.

‘But if you really need more, just let me know.’

That was the most reassuring thing I’d heard since February 29th, an eon ago.

Until someone newer joined the workshop, I would be responsible for floor sweeping and toilet cleaning two times a day. Would have been required to carry drinking water to the workshop every morning as well had I not been classified ‘3G’ — a category exempted from lifting heavy objects due to old age.

The janitorial task was kind of reassuring. I instinctively felt safer in a humble position. In my old-fashioned mind, nobody with half a heart would bully an old toilet cleaner, and a dedicated one at that. I scrubbed the disgusting bowls with patience and respect, and removed stubborn stains on the wall as if they had great archeological value. My toilet duty lasted only a few days. A newcomer took over with a sour face.

I had imagined prison work to be harsh and brutal. Pause to scratch, and the whip lands with a shattering crack.

I had been wrong. Prison labour at Tong Fuk wasn’t any different from most menial jobs — just something which had to be done because, like it or not, it had to be done. Comparing with regular jobs, it was actually less stressful. Performance had no bearing on job security or livelihood. There would always be food on the table, courtesy of the tax paying masses. None of us cared about promotion, and layoff was mere wishful thinking. Without any pressure to maximise profit, productivity, or personal bonus, the supervisors were also relatively stable, mentally speaking, than their industrial counterparts.

Unexpectedly, in the total absence of conventional incentives, there were quite a few conscientious workers, more than enough to prove academics in management theories wrong. Perhaps productive instincts laboriously selected over millennia still lurk in the gene pool? Perhaps these diligent workers, like me, understood that occupation speeds time up, and is therefore an effective mitigation? Naturally, not all my colleagues at Workshop Five shared this insight. Many were stubbornly remiss as a matter of principle.

Workers and slackers at Workshop Five coexisted in remarkable harmony. In a corporate environment, respectable colleagues find each other useless, or lazy, or dumb, or all of the above. And most of them are right. At Workshop Five, we didn’t judge each other by work ethics. Industriousness was a personal choice. Some enjoyed working rather than staring at nothing. Others preferred nose picking over sewing. To each his own. No one gave a damn. The workplace atmosphere was the most liberal and open I had ever experienced.

Surprisingly, the two technical officers in-charge were similarly accommodating.

Officer A was extremely helpful. He was always fixing or fine tuning or oiling sewing machines, tutoring anyone interested in learning the trade. His partnering colleague was the opposite. Glued to his chair, he preferred to risk thrombosis than waste energy shifting his bum. He read and reread the tabloids during his shift, announcing loudly which movie star was screwing who every now and then. When an inmate asked for help because a sewing needle had snapped, he’d tell him to ‘fuck off’ or ‘use your stupid fucking head’, something like that. Amazingly, his criminal negligence and preposterous indolence didn’t appear to bother his conscientious colleague whom I suspected to be an undercover saint.

Two times everyday, Tong Fuk’s top dog would make his ceremonial rounds with an entourage.

Their movement would be expertly tracked and communicated between all the workshops by phone. By the time they arrived at our workshop, they would not be able to find a filament of lint on the floor even if they went down on all fours to look. If I were the warden, I would have found that suspicious. I once mentioned this to a friendly guard, suggesting that the authenticity of the setting could be improved. He was baffled. ‘You’re saying we should keep the place dirty to look real, and invite shit from the warden? Dew Lay Lo Mo!’ Fantasies take precedence over reality even in a prison.

Upon arrival of the warden, the duty officer would shout: ‘Warden inspecting. Raise your hand if you have requests or complaints.’

We would spring to our feet and holler ‘Morning Sir,’ if it was the morning; ‘Afternoon Sir,’ if it was the afternoon. These greetings were quaintly offered in English. Even Uncle Tseng, a jolly senior Triad in his sixties, the only person I’d met since kindergarten who didn’t know the English alphabets, could say these two foreign phrases perfectly with a Chaozhou accent. During my tenure at Tong Fuk, I had not witnessed anyone venturing constructive criticism or complaints as invited.

It would be tempting to sneer at these daily charades. But inspection rounds were made twice daily, including weekends and holidays, rain or shine. Ninety nine point nine nine per cent of them were uneventful. It would be unrealistic to demand exactitude or stirring enthusiasm. Nonetheless, these predictable visits were a meaningful psychological deterrent to potential abuse. I was happy about their assuring reruns anyway.

Privatised prisons in some countries use captive labour for commercial contracts. Hong Kong convicts only work on internal projects, strictly non-profitable.

Workshop Five manufactured prison uniforms. My first assignment was to clip loose threads from nearly finished garments with a pair of truncated scissors. Annoyingly, with the pointy ends removed, the castrated blades were too blunt and wide for trimming itchy nose hair.

I started at the bottom of the pay scale. Two weeks later, I was promoted to the sewing machine. Perhaps my toilet cleaning had impressed the supervisors? I had never operated a sewing machine before, but liked it right away. I promptly became faster and better at it. A young Triad who sewed at Formula One speed noticed my progress and taught me a few useful tricks. Very soon, I was hemming over a hundred pairs of trousers an hour without compromising the details, or making one leg longer than the other. I was quite proud of this late-life achievement.

As the production line comprised workers and slackers, output was limited by the laziest guy in the room. Diligent labourers like myself could finish their daily quota in an hour or two, then chatted, read, wrote, or took long showers with a clean conscience. Reading was a more common sight in Tong Fuk than on university campuses.

I was gathering a cloud of loose threads with blunt scissors when my number was called: ‘365820. Grave sweeping!’

It choked me up instantly. Finally! A week had passed since the last visit at LCK.

I sprinted up the two hundred odd steps to Fingerprint Room, forgetting that I was a 3G inmate with creaking knees. Slippers snapped at my heels like man-eating ducks.

There was a long table with a glass partition in the middle. A few groups of inmates were whispering to visitors through phones. Satu and Fai sat on the other side, waving at me. Lantau was remote by Hong Kong standards. Handicapped by language barrier, it would have been difficult for Satu to visit without the help of my best pal and business partner. They say you only find out who your true friends are when in trouble. But I always knew.

The phones were not multi-channel like the ones at LCK. We couldn’t have a three-way conversation. Through the thick glass, I saw her badly mangled thumb nails. She had this infuriating habit of scratching them to the bone when stressed, or bored, or concentrating, or daydreaming. We cried and laughed a little, adjusting to seeing but not touching each other as best we could.

I had been on an alternate-day mood swing. One day I’d be calm and accepting, deriving job satisfaction from snipping threads, whistling as I scrubbed toilet bowls. Quite predictably, I’d be coming apart inside the next day while contriving a placid face. I would feel depressed, dangerously close to losing it. Another twenty six months seemed infinitely longer than eternity. Thankfully, being aware of this cyclic pattern helped me get through the bad days. Knowing that tomorrow would be better, I would go to bed early and look forward to a positive sunrise.

Today, unfortunately, was low tide. Even the visit couldn’t change that.

After spending the last vestige of positive energy, I deflated as I watched Satu and Fai leave the room. I wanted to smash something, or strangle someone, and decided that I will.

So fucking what! I’m in jail already!

At this fragile moment, a guard tapped me on the shoulder: ‘Time to go!’

Fuck off, arsehole!

I spun around, grinned ominously, and said: ‘Okay, Ah Sir. Thank you.’

About seventy inmates from Workshop Five were housed in three separate dorms, each with a capacity of twenty-eight. I was in Dorm L1.

We were rotated periodically between dorms for security reasons. Once in a while, sickness or misbehaviour would send a See Hing to the infirmary or the Water Rice Cell, aka The Hole in American prison parlance, for solitary confinement. In darker olden days, only plain water and white rice were served in Water Rice Cells three times daily — breakfast, lunch, dinner — hence the name. After a stint of watery detoxing, the transgressor would be transferred to a new unit, lest old animosities flare up on his return. Anyone sent to the hole was therefore gone for good as far as a workshop unit was concerned. A mainlander with an infamously short fuse and the character ren — restraint — tattooed to his right wrist had supposedly fought through all the units at Tong Fuk. His tattoo reminder evidently didn’t work. He eventually made it back to Workshop Five for a second tour, residing at L1. I found him nice and friendly. Just that he didn’t like being teased or bullied. Who does?

The entrance to the dormitory was a metal gate with double locks. A grilled opening adjacent the main gate facilitated panoramic inspection from the outside. The keys were supposedly kept separately by the duty guards and their colleagues from the previous shift. What would happen in case of fire, I wondered. The duty screws would need to run somewhere in a panic to retrieve the second key. I hoped it wasn’t too far away. Fortunately, there wasn’t much to burn, just cigarette butts, beddings, and us low-lifers.

The washroom was on display near the entrance, right next to the inspection grilles. It had two squat toilets. The one closer to the two headless showers had the usual open design. The second one, next to the wall, was screened off by two-metre tall panels fitted with a flimsy door, exceptionally private. On my first day, I spent more time in this cubicle than I needed to. It felt great to squat inside it by myself, away from the eyes of jail guards and convicts. A See Hing promptly noticed. ‘Shit there,’ he said, pointing to the next one. I asked no question and obliged. I soon learnt that the private cubicle was the ‘nightclub’, not meant for defecation or contemplation. More on that later.

Facing the nightclub entrance were two sinks unconnected to drain pipes. Water drained directly onto the floor before finding its way out of jail.

Social code at the dormitory was quite different from the outside world.

Littering was perfectly acceptable, no need to apologise. Junk food packages, half eaten buns, lit cigarette butts, phlegm globs half wrapped in tissues could all be tossed over the shoulders as casually as fishermen spit overboard. Each morning, a designated See Hing would clean up for three cigarettes per roommate per month. Cigarette was the currency for small conveniences and services. The guards turned a blind eye to this uncontrollable and innocuous underground economy unless it got overheated, creating a dangerous bubble like the real estate market outside.

Each night, two of the three rows of neon lights on the high ceiling would be turned off at about nine. If the kids were in a party mood, and they frequently were, their drinking game of room temperature water in lieu of alcohol, would continue. I adjusted to their rambunctious water carouse within a few days, and would fall asleep promptly with a small towel over my eyes, eardrums trembling. What gave me a bit of problem in the beginning was the hard bed, not the noise or the light.

Tong Fuk etiquettes were no more rational than country club rules. While partying could go on till late, toilet flushing was prohibited after the lights dimmed and before morning siren. Flushing was too noisy, partying wasn’t.

More than twenty prisoners snoring in the same room could be scary. I had done time in boarding schools in my younger days, and slept in big communal halls, but never heard snoring remotely as deafening. Extraordinary snorers were annoying but generally tolerated. Everyone snored after all. Very occasionally, they may get a rude shove in the depth of a vibrating slumber, or a loud Dew Lay Lo Mo scream from someone who had finally lost it, waking up half the room as a result, generating minor aftershocks of Dew Lay Lo Mos.

The noises escaping from the inmates’ dreams were often creepy. As dawn approached, someone would shatter the morning calm with eery moans or chilling shrieks as early birds exchanged pleasantries outside. The room would continue to sleep, or listen. Nobody ever complained about these shrieks. We all needed to vent bad vibes. I don’t know if I ever screamed in my Tong Fuk dreams. Probably not. One needs to have experienced being pursued by competitors brandishing meat cleavers to scream like that.

Tonight, I wanted to write about Satu’s first visit. Nothing came to mind. I was on my second notebook already. The first volume had been filled with catch-up observations and reflections. Since Lower Circle, I’d been keeping a journal instead, with briefer daily entries. I had managed more distance between my observations and personal experience as a prisoner.

I entered ‘goodnight, myself’ in the diary, then closed it. A bit melodramatic, but I was at the end of a very bad day.

I covered my eyes with the tiny washcloth. Since the first sleepless night at LCK, I had been sleeping surprisingly well. There was a saying among the cons: ‘Eating and sleeping well reduces the sentence by a third.’ Mmm, what if one dreams of solitary confinement in the Water Rice Hole night after night, or getting chased down the street by the police, or a chopper wielding competitor? To most cons, these dreams are more likely than sweet peaceful ones, which are probably a myth anyway. All my dreams are boring or frustrating, such as rushing to the airport to find the passport missing, or looking desperately for a toilet but every one I find is fully occupied by angry constipated people. In that event, sleeping well could even lengthen the sentence, or make imprisonment more unpleasant.

Young thugs were having yet another reunion tonight, repeating stories from their glorious teenage years at Tsim Sha Tsui at full volume. The guards were much more tolerant than boarding school prefects. Perhaps they preferred a lively dorm than a quiet sleepy one when they themselves had to patrol in semi-darkness.

Blearily, I heard familiar stories echoing back and forth, back and forth.

Most of them didn’t know each other before Tong Fuk. But they all had the same story, the only one in their universe: 'What’s-his-fucking-face called my fucking mobile, so me and fucking Fat Chicken and Ah fucking Chu went down to the fucking disco. Fat fucking Chicken was so fucking funny, I tell you man. Oh fuck, oh dear fuck. He asked the fucking guy who the fuck he fucking thought he fucking was. Oh it was so fucking funny! Oh fuck me man! We fucking chased him all the fucking way down fucking Prat Avenue…’

Ah, there’s a second one, much shorter: ‘Fuck me! You fucking know her too! Oh fucking Suzie. What a fucking pussy. I miss her fucking mouth. Oh what a small fucking world…’

Is it them? Is it the small fucking world? Or is it me?

I didn’t have an answer. Still don’t. I’m just a trespassing alien on this planet, confused.

Lulled by the happy sounds of social intercourse, I grinned behind my washcloth. Yeah, I landed at the bottom of the pit again. But tomorrow will be better, I knew from statistics.

Sweet dreams? Let’s try.

‘I fucking walked over, and smashed a fucking bottle over his fucking head…’

* * *

Next episode Black Bean and Tiger

Watchful eyes came not from the guards, but Black Bean and Tiger

Comments