Flower Lounge (11) Routine and Cuisine

- James Tam

- Aug 24, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

Somehow, humans fantasise themselves lovers of variety, serendipity, challenges, and, believe it or not, adventures. This romantic illusion, though far from true for the average person, has created an irrational discontent about a steady and predictable life such as the one we lived at Tong Fuk.

Steadied by penitentiary monotony, most days at Tong Fuk were predictable if not identical, seldom eventful. Unfortunately, not everyone appreciated repetitious felicity.

The morning siren was a bit loud. The deaf would have been woken by its vibration. A few youngsters would nevertheless hold on to their blankets and unfinished nightmares, and be defiantly asleep. A guard would come around momentarily to kick their beds, directing expletives at their mothers.

The rest of us, a couple of dozen dreary and grumpy convicts, dragged ourselves to the toilet, one hand holding the outlet of a pressurised bladder, yelling: Fai Dee Lah! Dew Lay Lo Mo Hai — hurry up, and blessed be to your mother, and so on, as usual, et cetera. Water and urine splashed freely. Coughing, spitting, and swearwords bubbled through toothpaste, charging the room with raw energy.

Momentarily, the gate unlocked. A uniformed guard of honour awaited right outside to welcome us to breakfast. Filing past them, shrouded in industrial dentifrice, discharging overnight phlegm and flatulence, cons squinted against a hot new day with disgust, or moaned about the cold spring rain. To prisoners and teenagers, the day was never quite right.

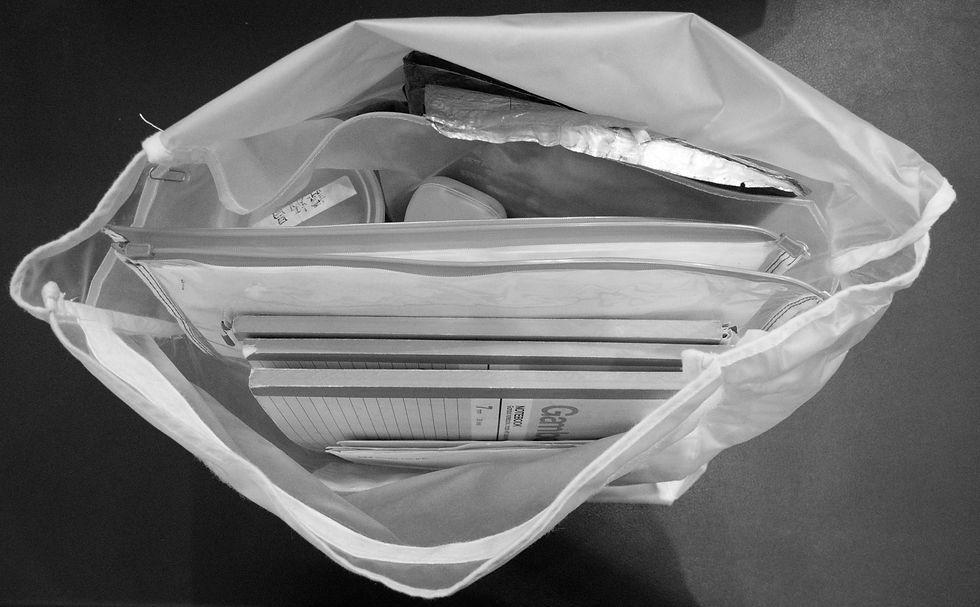

The guard of honour looked into our carrying bags for anything out of the ordinary, knowing that nothing would be out of the ordinary. Formalities were imperative to reinforce discipline and respect.

A less-than-one-minute walk took us to the dining hall. Where else? While waiting for everyone to settle, prisoners yawned loudly. Soon, the room would be filled with the sound of yawning, like a band of musicians tuning their instruments before the show. Wishing each other good morning wasn’t necessary. In fact it would have been queer to wish anyone good morning. The first meal of the day commenced after a careful headcount. Invariably, not just typically, it would be squash and rice garnished with a bit of meat. After a slow breakfast, the rest of the morning would be dispatched perfunctorily with half-hearted labour.

Lunch was light, long, lazy, and lousy, distracted by television. As we ate, recycled soaps provided entertainment at full volume. These noontime replays at Channel Tong Fuk were not amusing, or silly, or funny, or ridiculous, or beautiful, or inspiring, but See Hings watched them with zen-like focus. TVs kept prisoners anchored more effectively than cast-iron balls and chains, but were noisy even without being dragged.

A few inmates were extraordinarily pious. One of my table-mates spent a good ten minutes uploading gratitude to God before each meal, while us heathens chewed. I actually regard saying grace before meals one of the most meaningful religious practices. Too many of us take food for granted, and waste without a second thought. However, their extensive mumble-jumble pre-meal ceremonies might have invited derision or medical attention out in the free world. Convicts were commendably open-minded without making any self-conscious neoliberal claim about being open-minded.

After a long lunch, we returned to the workshop for more half-hearted labour.

Playground time started at about four. At school, I had once been forced to play football, like it or not. Tong Fuk was more liberal; football was voluntary. I did Zharm Zhong — a stand-up meditation — instead, and let my mind rove.

Dinner time. We ambled back to the dining hall like privileged school boys returning from polo, chatting in good spirits, swearing, feeling hungry, trying not to think about deep fried fish.

After dinner, we lined up outside the dining hall to be searched by officers armed with metal detectors. A basket of gooey cloudy buns and a bucket of syrupy milk powder solution awaited us en route to the dorms. Hadn’t we just eaten? Yes we had. But the CSD wanted to make sure that we were adequately fed, probably in compliance with some international convention. The milk drink, supposedly imported from Germany, had a concentration camp feel to it. It was sadistically sweet, and gripped the tongue on contact. Most inmates declined, but the ritual persisted. It had been like this for many years. After we have all filed past, they would pour it down the storm drain.

A typical evening at Tong Fuk was more studious than boarding school. Half the prisoners would read, write, or listen to the radio with earplugs, or play chess furtively (chess was not permitted without supervision due to gambling concerns). A few would exercise, pushing their torsos up against gravity repeatedly, or lifting the water buckets again and again. Muscles to gangsters were like neckties to bankers, not necessarily useful for the job, but essential for the image.

Young cons livened up the dorm with rowdy games and routine shenanigans. Each night, they traded junk food with the quarter across the hallway. Bags of chips and whatnot were tossed back and forth across two layers of bars. Why did they exchange confections abundantly available on both sides? Just for fun, I suppose. There was evidently a functional honour system to record these hectic inter-cell transactions, as disputes were rare.

Meanwhile, young prisoners took turns visiting their ‘nightclub’.

Night-time activities eventually gave way to collective snoring. Everyone was one day closer to discharge. Tomorrow will be largely the same. The only variables would be the three main meals which differed from day to day according to a weekly recurrent cycle.

Inmates were well-fed in four daily instalments: breakfast, lunch, dinner and bedtime snack. For slammer grub, the meals were very reasonable, balanced and generally of good quality, albeit mysterious in parts. The menu was precise and consistent. One knew exactly what will be served for dinner tonight, tomorrow, and the third Thursday nineteen months into the future, assuming one would still be in jail. Not everyone enjoyed such a high degree of predictability, however. Some took the perpetually recurrent menu as a subtle form of punishment. It didn’t bother me though. Since retirement, I had been eating the same dish for lunch most days at home — bean sprouts with fried tofu pockets and rice.

The cyclic menu, repeated weekly for as long as anyone knew, is reproduced as follows. I hope it’s not classified information:

Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | |

Mon | Pork, squash, rice | Sweet red bean gruel + bread | 2x Chicken wing (mid-section), veggies, rice, orange |

Tue | Beef, squash, rice | Salty peanut gruel + bread | Fish! hardboiled egg, veggies, rice, orange |

Wed | Chicken wing, squash, rice | Sweet mung bean gruel + bread | Fish! fried tofu (tofu pok), veggies, rice, orange |

Thu | Composite pork meatball, squash, rice | Salty soya bean gruel + bread | 2x Chicken wing (mid-section), veggies, rice, orange |

Fri | Beef, squash, rice | Sweet peanut gruel + bread | Fish! hardboiled egg, veggies, rice, orange |

Sat | Chicken wing, squash, rice | Salty tofu skin gruel + bread | Fish! veggies, rice, orange |

Sun | Composite beef meatball, squash, rice | Sweet milk tea (a highly popular treat) + salty purple bean gruel + bread | Fish! fried egg, veggies, rice, orange |

Breakfast was squash, always squash, randomly chopped up. By the way, squash butts are actually edible and harmless, just a bit woody.

The British gave European and Indian prisoners special treatment. This accommodating tradition had been gradually extended to other minorities. Special meals could now be requested for ethnic, religious or health reasons. ONs (foreign inmates) ate bread and cold greasy eggs for breakfast. Muslims ate pork-free dishes prepared in a profanely non-halal kitchen, flavoured with Indian curry. It seemed that those in charge of the prison community couldn’t tell the difference between halal and curry, and believed that anyone from west of Lantau Island ate curry. I actually lived west of Lantau, and loved curry. These days, the cons could also request beef-free or vegetarian meals. A diabetic See Hing told me that they were fed essentially regular meals with most of the flavours extracted.

Vegan and peanut-free options were not available. Folks allergic to wheat or peanuts better not break the law. That said, CSD meal service was already more considerate and diverse than some airlines. Once a choice had been made, however, no change of mind would be entertained. I once asked a friendly officer if I could switch to vegetarian for a while (curry would have been nice but that required a change of ethnicity or religious commitment). He gave the standard answer rhetorically: ‘Does this look like a fucking hotel to you?’

‘Ha! No lah, Ah Sir,’ I laughed at the highly predictable reply. ‘This is Flower Lounge. Much classier.’ He laughed too.

Of the three main meals, lunch was the most disagreeable. In the above tabulated menu, the atrocious word gruel appears seven times in the middle column. That’s right, seven times. Once a day, a medieval gaol gruel was served. Watery gruel was ladled straight from a plastic bucket (the kind one finds in wet corners of public lavatories) on the floor into our multi-purpose mugs. We then picked up a thick slab of generously buttered white bread. Occasionally — without a recurrent pattern — a smear of tasteless and odourless brown stain would appear on top of the butter. See Hings told me it was fruit jam. I had my doubts; it didn’t taste anything like jam.

I had been reminded on numerous occasions that Tong Fuk was a prison, not a five-star hotel. Taking this hard fact into account, the meals were actually quite good. Yet, inmates grumbled, which is understandable. They were remarkably creative in jailbreaking the seemingly insurmountable menu. The office boys at Fingerprint Room made fantastic toasts with an electric iron.

Back at the dorm, cheesy onigiri — Japanese rice balls — were the young thugs’ favourite.

Recipe: 1) Plain rice smuggled from dinner 2) Mix rice with crushed Cheetos — an industrial cheesy puff 2) Mould by hand into fist-size balls 3) Place rice ball inside all-purpose mug 4) Warm with hot water in the toilet.

Disgusting. But I salivated when the smell of cheese and rice emanated from the toilet sink. That’s what imprisonment could do to a person.

On the wall separating the kitchen and the dining area was a slot at waist level. A See Hing in the kitchen would scoop gravy onto a wobbly plastic plate of food, then push it through the slot onto a ledge at our side. The server could not see his customer on the other side.

Gravy was one of a very few things a prisoner could exercise freedom of choice. As we stood before the food slot, we yelled out our preferences — no gravy; little gravy; extra gravy, please! One Tuesday morning (beef on Tuesday mornings, see table above), having survived the previous day and renewed my confidence in life, I was in frivolous spirits. When my turn came, I extemporaneously requested medium rare please! Haha, that was fun. Not knowing how to respond to my request, the system hung. A couple of worldly jailbirds giggled. Sensing the serving inmate frozen behind the slot and the duty guard’s reprimanding stare, I panicked.

‘Sorry, sorry. Sorry See Hing, just joking. Little gravy please.’

Luckily, the system promptly rebooted. The duty officer kept up his dirty look at me for a few more moments: ‘Playing games, huh? Ah Cheong!’ He knew that the old guy Ah Cheong could be spontaneously facetious.

‘Just kidding, Ah Sir, my apologies.’

Luckily, he ignored me and looked away. Phew.

One had to be careful and tactful with jokes in this place. Trying to be funny was in principle okay, even welcome, provided that the joke was funny and, more importantly, readily understood, and absolutely impersonal. I had witnessed convivial discussions abruptly turning abusive, even violent, because of a wrong choice of word. It was not necessarily bad humour. Many of the fellows had hidden sensitive spots which even the owners were unaware of. Accidentally poked, it could explode like a land mine from a past war. Sarcasm, my absolute favourite, had no audience in Hong Kong in general. In jail, it should not be attempted under any circumstances. I understood the enormous risk involved without the Guardian Angel whispering. The slightest obscurity — such as my medium rare request — could have been misunderstood and resulted in an unpredictable response. That was stupidly risky, and really not that funny. I self-criticised as I walked back to the table, beef and rice in hand. Never pull anything like that again for as long as I’m in jail, I promised myself.

When I first arrived at Tong Fuk, I ordered extra gravy for lubrication. About a month on, I switched to little gravy. I was suffering from dizzy spells, and suspected that the salty slush was responsible. I had not had a body check up since nineteen, not even a reading of blood pressure or sugar level. One day, I finally decided to consult the medical officer at the infirmary. It turned out that my blood pressure was 74/114, assuming his machine was functional. In his pseudo-professional opinion, it was better than most young thugs. He prescribed two little pills anyway. ‘Twice per day for a week.’ They worked as miraculously as the boil ointment at Lai Chi Kok. In two days, my dizziness had stopped. I asked the officer what the miracle pill was as he fed me another one at the dinner hall. ‘Vitamin C,’ he winked, a finger above my tongue.

‘So,’ I said after swallowing and showing my tongue for inspection. ‘It was Vitamin C deficiency. Good diagnosis!’

Breakfast was my favourite meal of the day. Lunch was horrendous mainly due to a personal dislike of bean gruels; they were quite popular in general.

The only universally detested dish was dinnertime fish. When a child, my mother used to force-feed me vomit-inducing omega fish oil. She was otherwise a kind and loving person. The fish at Tong Fuk tasted much worse. Unfortunately, fish prepared the exact same objectionable way was on the menu every night except Monday and Thursday. Though we knew with absolute certainty what was coming, there would be a faint collective sigh when the first fish, doused with gravy, slid through the slot.

These cat-spurned minnows were about the size of the middle finger of a short fat person. I suspected they were deep-fried hours before dinner, then left in open air to absorb moisture while oil drained, and the carcasses turned limp. Small fish with countless tiny bones scattered throughout the body are puzzling. These fine bones are not attached to any discernible structure, therefore obviously not serving a physiological purpose. The Tong Fuk fish took this biological mystery to new heights. They had more bones than meat. What could have been their anatomical function? These embedded splinters must have hurt when the poor creature swam. What was God thinking when he designed this one? Or was He giggling sardonically? I ate each and every one of them anyway. It was a form of physical challenge and spiritual disciplining. My late father had taught me to never waste food. Eat whatever’s served. Never complain about food. I wonder if he would have made an exception for Tong Fuk fish.

The teeny chicken wings tasted surprisingly good, even organic, perhaps free-range, but nonetheless perplexing. They were super small, evidently removed from XXXS spring chickens. What did they do with the rest of the baby birds? I’m sure there wasn’t a market for miniature wingless chickens. Had never seen one anyway.

Thursday pork and Sunday beef balls were mushy and slippery and indistinguishable from each other, but kind of tasty. However, they didn’t resemble anything originating from a pig or a cow. I’m not one of those inquisitive individuals who must first clarify the biological, nutritional, and molecular composition of everything before putting it into their mouths. But I was a hobbyist conspiracy theorist, and my faith in the government was at a low ebb. Looking at these composite meatballs, my first association was tumours removed in operation theatres, though I had never seen one. What exactly do they do with these clinical wastes, I wondered.

‘This menu was designed by a dietician from the department,’ an inmate told me. He was a regular, and knew how things worked.

‘When?’ I asked, as if it mattered.

‘Ooo, long ago. Always like this.’

Was the dietician still employed? If he was, then what the hell had he been doing all those years. Let’s assume he once laboured slowly and surely to create this delicately balanced diet in six days. On the seventh, he rested. Job well done. Then what? If he had retired, then what would his successor do to kill time in the office as we prisoners ate in accordance with the historical menu?

* * *

Next Episode Nightclub

Comments